I want to tell you about my old solid oak door through the thoughts that I had while restoring it for over a fortnight.

Our terrace house was built circa 1678 but I don’t know when the door was crafted. The house is made of stone, probably carted down from Hadrian’s Wall, four miles north. The oak door is one of the last handmade artisan doors left in the street. It has character and it is hung on the wrong side.

Below are some of the things I thought about.

A seedling survived

The acorn that germinated and became my oak was spared a gall wasp that would have made it infertile and disfigured. Then, the young seedling made it through nibbling deer and disease. As a young tree, it managed to grow up (presumably protected by its mother*) into a tree large enough to make a door.

Oxygen

Recently I read that a single tree supplies oxygen to four people. 1:4. So my oak tree gave breath to four people at a time, over a span of maybe 15 or more generations, if it lived for 600 years.

Age and history

There are many annual rings on my door. Oaks can live up to 1000 years. So my door’s tree may have witnessed the feudal system, knights in shining armour (Langley Castle is just a mile up the road), maybe the English civil war, and more events thereafter, before it became a door.

Ink and the written word

From Roman times until the 19th century, black ink was made from tannin rich oak galls*. Just think of the rich written legacy that resulted. Holy scripts, Shakespeare, and the early printers relied on those galls.

Wildlife

Insects

Oaks can support more than 200 insect species, supplying vital food to insect-eating birds and animals.

The gall wasp

We can thank the humble gall wasp for the ink noted above. When a gall wasp lays an egg, the oak makes defensive cells around it, forming a gall deformity. Inside the the gall, the larva develops and pupates into a new gall wasp. In the Autumn people harvested galls to turn into ink. (I have added a link to this process at the end of this blog.)

Animals

I imagine my oak tree began its life well before modern times. This being so, it may have been home to red squirrels (now pushed out by American grey squirrels) and the once plentiful pine martens. Some wild boar might have rootled for morsels below. Perhaps a wolf passed by or a lynx hid there. And who knows how many nests were built to renew bird populations. My oak may have supplied flowers to hungry dormice in the spring.

Shade plants

The wood wide web

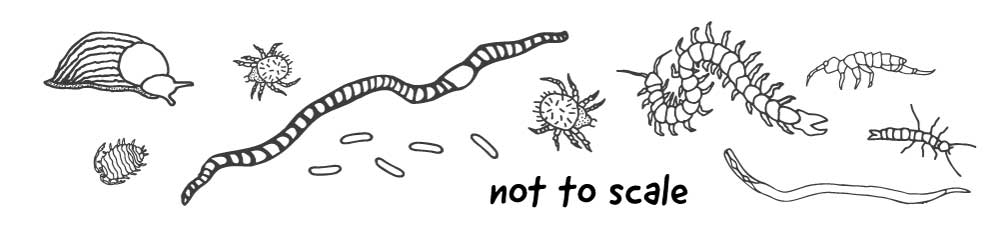

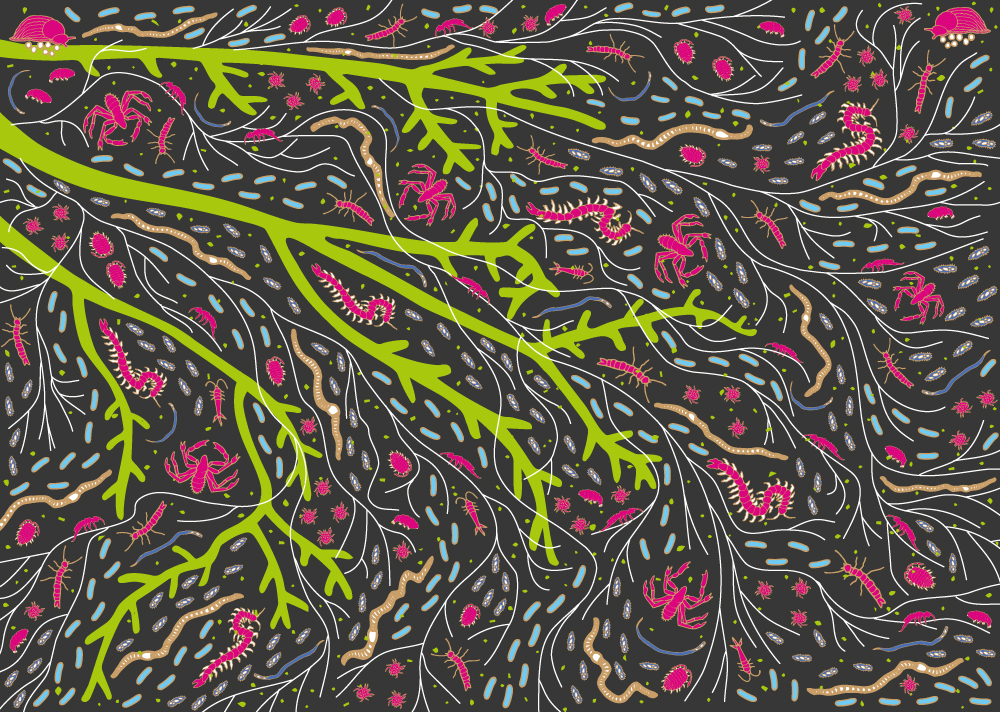

My oak would have belonged to a wood wide web. This is made up of a vast network of mycorrhizal fungi (represented by the white lines in the design above). Within this network complex relationships are built between trees, plants, micro-organisms and the soil below.

Mushrooms

The wood wide web, probably, popped up chanterelles, honey mushrooms and red fly agaric mushrooms in the autumn. The people nearby in all likelihood gathered the honey mushrooms and chanterelles and cooked them in butter for a tasty autumn treat.

Woodsmen (they probably were men)

A woodsman would have picked my oak and used an axe to cut it down. The oldest, biggest oaks were used for churches and cathedrals, so my oak was probably smaller and easier to fell. And then there are the skills to season the wood and make the door. It’s taken me two weeks to restore my front door, and I’ve felt that I haven’t the time to spare. (I really need to work on my new design collection.) So who ever made my door was patient and meticulously accurate with angles, numbers and safety.

The Earth

All the above would not have been possibly without the unique place the Earth occupies in the Universe. Being a tilted planet, we circulate the sun once a year at an angle that gives us seasons, solstices and equinoxes. Over four and half billion years of light, combined with water and gases, our ball of rock got cellular and then multi cellular life. With plants and trees, we got oxygen and energy rich plant food for hungry air breathers: birds, animals, you and me.

As I sanded and cleaned, treated and oiled I generated all these thoughts. I do this quite often with objects. It can be a tap, or a dress or a cup of tea. It makes me feel rich and grounded, with a sense of belonging, wherever I find myself.

* A mother tree is a real thing. Mother trees send signals to their young through chemical reactions and via the wood wide web of mycorrhizal fungi.